Artificial Imitation: Did John McCarthy get the term AI from Norbert Wiener?

Serendipitously exploring history to inform the future

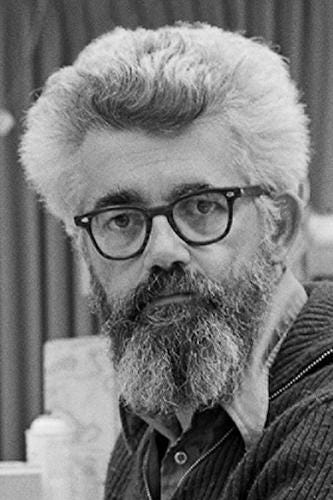

Everybody that cares knows that John McCarthy coined the term “artificial intelligence” or “AI” in Aug of 1955 in his joint proposal for the 1956 Dartmouth workshop on AI. This is how it is recorded in history (though many incorrectly note Sept 1955 or even 1956 as when he first used the term), and this is what he claimed - except for one time. In 1974, while recording an interview with Pamela McCorduck for her 1979 book “Machines Who Think”, McCarthy noted, "I won't swear that I hadn't seen it before - a vague memory that someone else had used the word.” After several years of looking for what might have been McCarthy’s source for the term, I recently found a potential suspect in a lost lecture of McCarthy’s nemesis, Norbert Wiener. While not quite a smoking gun, there seems to be enough probable cause for a gunshot residue test and some further investigation. Given McCarthy’s reactionary narrowing of the field of AI from Wiener’s interdisciplinary cybernetics to a narrowed engineering approach that still dominates, it may be a useful exercise beyond historical curiosity to head down this rabbit hole.

Flirtatious Reveal

Why would McCarthy, who proudly owned the moniker of the inventor of the term AI, give a different account this one time to this one person? He was probably flirting and letting his guard down. On record.

McCorduck was a writer, journalist and English professor who happened to focus on AI almost from the beginning of its inception and throughout her career. In 1960 as an undergraduate at UC Berkely, she signed on as an assistant to Feigenbaum and Feldman’s effort to develop the first AI textbook, “Computers and Thought”. After this effort, she became an assistant to Feigenbaum at the AI hub of Stanford in the mid-60s, where she met and interacted with numerous first generation “godfathers” of AI. One of these was John McCarthy. They were friends as she describes it in her 2019 memoir, “This Could be Important: My Life and Times with the Artificial Intelligentsia”, with their interactions revolving around not only AI but music, counterculture and even one awkward coffee date he invited her on in 1968, shortly before she left for New York. From McCorduck’s description:

“After a while I said, “You are considered - odd.”

He gazed at me in silence, and I was sure I’d offended him. Finally he said, “No. I’m just shy.”

I had no words for that disarming self-disclosure.”

As the first AI winter settled in, McCorduck was considering an oral history and book project on the first couple decades of AI. In 1973 she went back to Stanford to refine the idea with Feigenbaum and McCarthy. Once it was funded, McCarthy was one of the first interviews she conducted in late 1974 and early 1975. It was here that he made his revelation to her of “a vague memory that someone else had used the word.” While McCorduck describes the exchange in her subsequent book, “Machines Who Think”, there is also audio recording of the exchange in her records that she donated to CMU Archives upon her death in 2021. The McCarthy interview transcripts and recordings are limited for research purposes only (I’ve been slowly working on a screenplay for a currently unfunded documentary on her book with another English professor, Sharon Dilworth, at CMU), but I’ve listened to them. McCarthy appears to still be trying to impress her and capture her interest, here with what appears to be a vulnerable revelation that also enhances the content of her book research with a bit of mystery.

Low Level Mystery

I was intrigued when I first heard it, but also a bit perplexed. The book came out in 1979 and was reissued for its 25th anniversary in 2004, long before I started looking at this. Wouldn’t someone already have found that source if it was available? Even if it wasn’t a direct borrowing of the term “artificial intelligence” but some derivation, wouldn’t current popularity of the term that dominates a popular and profitable area of practice draw some curious historical detectiving? Granted, it is more historical curiosity than anything, but historical curiosity is a driver for many things in this world. Wouldn’t someone who might have had the term borrowed or derived also have incentive to speak up for at least some partial credit? And another curious aside, why did McCarthy say “the word” and not “the term”?

These questions didn’t exactly haunt my dreams, but the more time I spent looking into the pre-history of AI before the Dartmouth workshop in 1956 the past few years, the more it nagged me. McCarthy was no doubt brilliant, from creating the computer language LISP to time-sharing in computers, he was indeed a critical practitioner of the art of AI for its first generation. Yet he was also a consummate hype-man who was known for trying to steal credit from others. Nobel prize winner Herb Simon, who along with Alan Newell and Cliff Shaw created the only operational AI program presented at Dartmouth (though it was functional several months earlier and had been previewed to McCarthy at CMU before they were invited to the 1956 Dartmouth meeting), noted to McCorduck the lengths they had to go to avoid McCarthy stealing their thunder. As I touched on briefly in my essay “Machine Intelligence is not Artificial - Part 6: Dartmouth 1956, The Birth of AI and the Balkanization of Machine Intelligence”:

“Trouble was brewing leading into the September IRE conference at MIT, as McCarthy wanted to present on the outcomes of the Dartmouth meeting, including Simon and Newell's Logic Theorist. They were upset by this and viewed it as McCarthy trying to take credit for work they had already completed before the Dartmouth meeting. Simon recounts to McCorduck that there were some challenging negotiations about who would present what at MIT, with the session Chair, Walter Rosenblith (a colleague of Wiener's), mediating the negotiations with the group as they walked the streets of Cambridge before the event. In the end, McCarthy gave an overview of the Dartmouth meeting and Newell presented on the Logic Theorist program Simon and he had developed along Cliff Shaw (who was at RAND on the West Coast and didn't attend either meeting).”

It was also the case that McCarthy’s inspiration for the 1956 Dartmouth event was his reactionary desire to narrow of the field of cybernetics, which he felt had factored too prominently in the “Automata Studies” collection he and Claude Shannon had edited in 1953-55 and was published in 1956. McCarthy complained to McCorduck he was, "very much disappointed when most of the papers that we received were, in fact, about automata, and were not in my opinion any contribution to artificial intelligence [he notes earlier in the interview he wasn't yet using that term in 1954]." He goes on to note, "The original idea is that he [Shannon] would be the big name and I would do the work, but it ended up that he did the work too.... One of the reasons why he did all the work is I was unenthusiastic about the papers." More than half of the papers had come from cyberneticists from the British Ratio Club and U.S. Macy Conferences (which his co-lead Shannon had also attended as a visitor). Even the declination to submit a paper from Ratio Club member and machine intelligence pioneer Alan Turing (who had detoured into morphogenesis by 1953 when the invitations went out) promised to “return to cybernetics soon”.

McCarthy wanted to focus on intelligence, as Turing had in his famous 1950 paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”. He tried to change the name of the “Automata Studies” collection to “Towards Intelligent Automata”, which Shannon rejected for having too much bombast. He wanted to do this by narrowing the aperture only to digital computing solutions for human-like tasks, avoiding the multidisciplinary complexity of cybernetics. More importantly he wanted to avoid Norbert Wiener, the founder of cybernetics. He went to great lengths in his discussion with his potential funders from the Rockefeller Foundation in the Spring of 1955 to avoid having cyberneticians invited to the Dartmouth workshop, though he was made to accept a few. The petty politics of the day underscored a deeper conceptual division between the camps, the ramifications of which are still with us today.

McCarthy noted in a 1988 interview, "...one of the reasons for inventing the term 'artificial intelligence', was to escape association with 'cybernetics.' Its association with analog feedback seemed misguided, and I wished to avoid having either to accept...Wiener as a guru or having to argue with him."

The coining of the term “artificial intelligence” was not well received either by McCarthy’s cofounders of the conference like Shannon, or by attendees like Simon and Newell who even decades later preferred the term complex information processing or other less showy terms. Simon noted wryly to McCorduck, “we were doing AI before [Dartmouth], we just called it operations research.” Nonetheless, McCarthy got his way and the rest is history, with all manner of math and computing now being marketed for billions and trillions of dollars under the name AI over the last half century, despite us having weathered two AI winters along the way. Meanwhile Wiener’s cybernetics has largely been downgraded to a cultural phenomenon and linguistic prefix for all things computer related, despite Cold War wranglings behind the scenes that at times makes the current AI battles seem quaint and bloodless.

What’s in a Name?

How and where this term may have originated is both historical obscurity and yet possibly foundational to the thematic distinction between between what was and what is with respect to machine intelligence. I considered that McCarthy’s potential source was probably obscure and not easily findable from modern search efforts, otherwise someone would have come across it. The term was either a derivation from something he heard, or possibly an out-of-context alteration of a different idea vs. a straight copying of terms. Its source was likely unaware of how the term blossomed, or for whatever reasons did not care. Coming from the relatively small community of cybernetics, machine intelligence, automata, computer brains, etc. seemed unlikely since it was a relatively small group across even the five different factions Newell laid out in his 1957 thesis: 1) engineers, 2) AI engineers, 3) cyberneticists, 4) cyberneticists + digital computer analysts, and the 5) information processing group.

My first thought was science fiction, in part because just prior to bringing up the mysterious potential source of the AI name to McCorduck, McCarthy mentioned his love of sci-fi at the time. Fascinating stories and non-fiction discussions of machine intelligence were happening in the late 40s and early 50s, often under pseudonyms, in the pages of pulp sci-fi magazines like Astounding Science Fiction. The running dialogue in the letters section alone warrants review by anyone interested in the back channel development of the idea of AI before we ever got AI as a name for it.

My initial searches bore no fruit on the possibilities of McCarthy’s source or inspiration, though were never wasted effort. Finds like a Bell Labs scientist publishing non-fiction outlines for machine intelligence under a pseudonym months before Turing gave us his own take on it in his 1950 paper were priceless from a curiosity perspective. Yet nothing appeared that seemed it might have been reimagined by McCarthy for AI. The time window where it seemed the term entered his lexicon was small - he wasn’t using it in April 1955 for the conference, but by August 31st 1955 had used it for the first time in recorded history in the final draft of the Dartmouth proposal. He had talked about starting to read sci-fi magazines in the early 1940s, and having many copies of older issues, so I couldn’t be certain he hadn’t stumbled upon it from older material. My investigations were fun, fascinating and slow, but to no avail. I had not completely written off the possibility that the term came from something more immediately relevant to the that social/ intellectual circle at that time, there are no shortage of stories in the gaps in monitoring all of science in the pre-internet search engine era, but it seemed unlikely. I was aware that sometimes things get missed, even in heavily covered histories - I was able to find a CMU (CIT at the time) lecture from Wiener in 1949 mentioned in the CMU archives that wasn’t listed in the MIT archives of Wiener’s outside activities including guest lectures. My work across the two archives groups to get this added a couple years ago reminded me that we are dealing with partial information when looking at the not so distant past - especially when we rely too heavily on lazy language models of today and the limited data they are trained on.

I persisted.

Wiener’s Lost Lecture

I’ve had the good fortune to have returned to academia this year as adjunct faculty at Duquesne University’s Psychology Department after a 15 year hiatus. My time in government and the tech industry have left me with new perspectives, new questions, and lots of catching up to do as I engage the next generation of students. In advance of my Fall course, I was in the wonderful Duquesne library last week, collecting some books on phenomenology while also exploring what they had on some other topics, like cybernetics. There on the bottom shelf, near Pekelis’ “Cybernetics A to Z” (I’m way overdue to dive into the post-Stalin Soviet cybernetics), I found an odd, thin item on the shelves. Given where it was in the stacks, I had to check it. Upon opening, I was a little stunned and pleasantly surprised to find a pamphlet of a Norbert Wiener lecture.

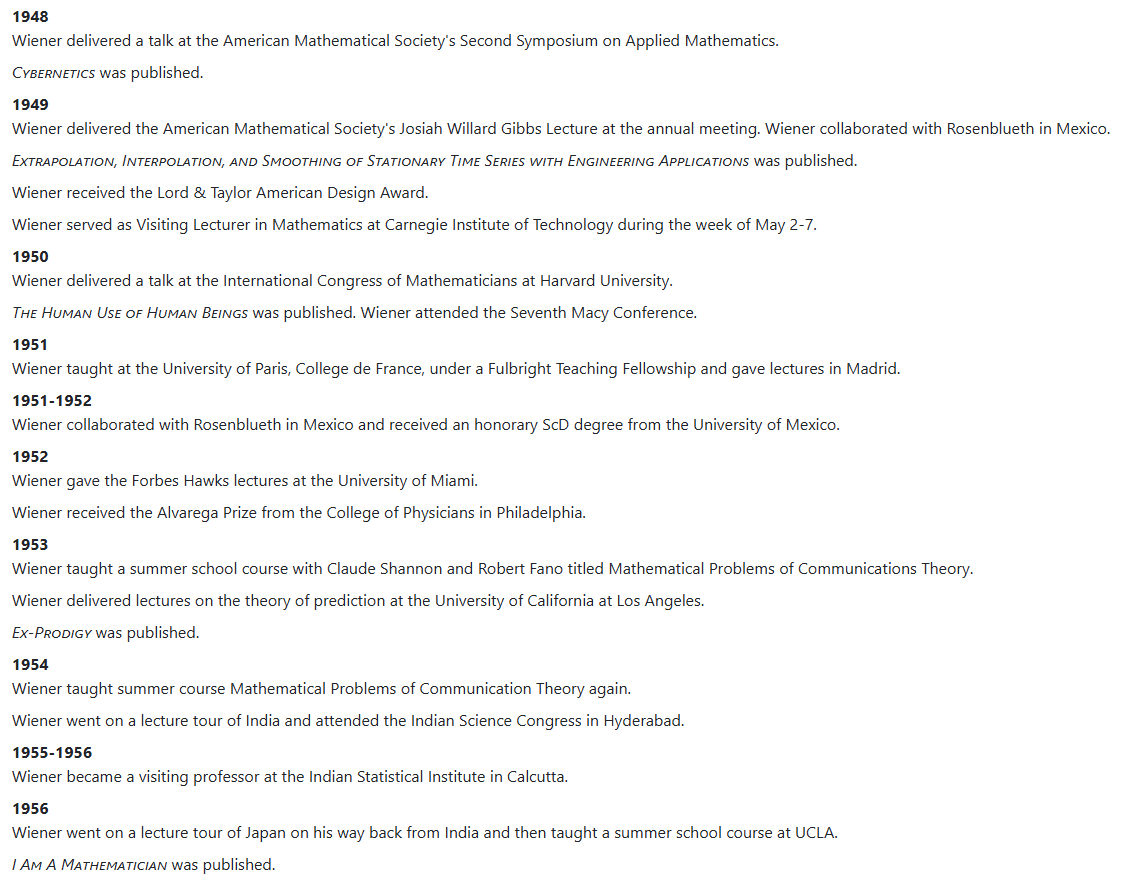

In the past several years studying this man and his many forgotten contributions to history, I had never come across this publication, even as a reference. Despite reading every book and many articles about him, combing through an array of cybernetics related materials from different eras that referenced him and his works, and even helping to add to the archival knowledge of him at MIT, I hadn’t seen or heard of “Time and Organization” before (note: I’m not the only one who hasn’t heard of it, I have since learned. It does appear to be in the archives as a miscellaneous title. It is not noted in his timeline as a guest lecture however - see above).

This lecture was delivered on June 2nd at Southampton University in England as part of the Fawley Foundation’s Science and Industry lecture series, though I have since learned it was originally scheduled for a week earlier in May. Wiener and his wife had traveled by boat from Boston to the U.K. as the first stop on an 18 month journey that had him guest lecture for extended periods in India and Japan, with shorter stops in England, Germany, Israel, and finally at UCLA before returning to MIT in the Fall of 1956. This 1955 lecture was printed as a pamphlet shortly after (or possibly before) it was given. I am still trying to determine the specific publication date, though I have found evidence that by September of 1955, it was already being prepared for translation into Japanese as part of a collection in advance of his arrival there. I am also seeing if I can get permission to share the brilliant content of this mere 16 page document. It was small enough the Duquesne library saw fit to give it its own carboard binding.

As I read this document, I had no expectations it might be a possible lead to the inspiration for McCarthy’s AI term. To be honest, upon first read I thought it was an interesting aside and paid little attention to the date, location and surrounding context. Yet as I read it, I started to sense where it was headed and began wondering if it contained any surprises. It did not disappoint.

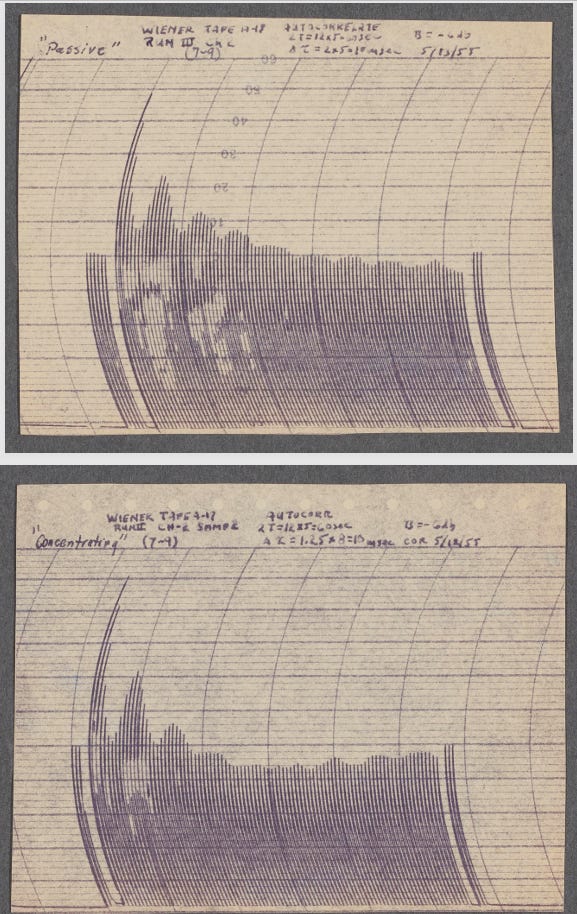

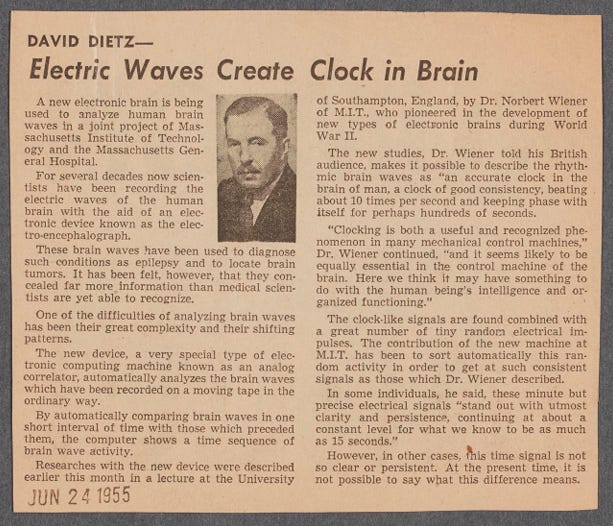

The lecture itself relates to work Wiener was doing with researchers at Mass General relating to timing and organization of brain activity. The brain’s “clock”, as described in Boston (?) media coverage about the lecture (above, from the MIT archives), “may have something to do with the human being’s intelligence and organized functioning.” During the lecture he discusses the social and civilizational value of clocks and coordinating activity. He ties this into the brain’s own coordinated and synchronous behavior.

As he wraps up his lecture, Wiener uses language that may (I stress MAY) have inspired McCarthy’s choice of the term “artificial intelligence” a few months later for the Dartmouth conference.

After describing the value of time coordination at a society level being important, he notes the examples of Lent and Ramadan which are not fixed to a specific time point in relation to the seasons. “Their clock is artificial,” he notes, “and not the strict clock of the seasons.”

A paragraph later, after tying aspects of our sociological clocks to those “clocks” found in the brain he concludes, “It is quite conceivable, although not yet proved, that the regularity of the human clock will be associated with intelligence, and with the ability of the intelligent man to carry out relatively long-time coordinated mental activity. Of course this does not mean that the clock itself is a measure of this intelligence; but at any rate it gives us a strong suggestion that the regularity of this clock may be necessary if not a sufficient condition for highly organized mental activity.”

I’m not suggesting that McCarthy was necessarily inspired by Wiener’s ideas, but it seems that the language he chose to use in his August 1955 proposal, artificial intelligence, may have been influenced by this same language used in Wiener’s June 1955 lecture. I have more detail to dive through with respect to the timing and distribution of this lecture, along with potential conduits of information to McCarthy that summer, as he did a fellowship with IBM and settled in for the Fall at Dartmouth.

McCarthy potentially deriving the term AI from Wiener would be both historically fascinating and richly ironic, given his efforts to distance himself from Wiener’s ideas.

There’s also, as noted by my Neuroboros colleague Ami Elliott, a deeper level to the irony. If it turns out this influence of Wiener on McCarthy’s choice of the term AI pans out this may be an indication of a pathological avoidance of more broad focused efforts towards machine intelligence that continues to be the intellectual legacy of McCarthy’s AI, even today.

I’ll be continuing to work to connect these dots. This will be tedious work with travel to dive into paper archives covering the activity and correspondence relating to several joint colleagues of Wiener and McCarthy. If you enjoy this work and would like to support it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. I’ll make my initial findings available to paid subscribers, while working towards an open access manuscript on these matters of history, curiosity and potential relevance to the future of machine intelligence!

"...attendees like Simon and Newell who even decades later preferred the term complex information processing or other less showy terms."

Do you have a comprehensive list of some other preferred terms available in any of your essays, or that you can point me towards elsewhere?

Thank you for this